To avoid litigation, the city agreed last year to provide better training of officers and require them to keep records of all stops beginning January 1, 2016, showing which ended in arrest and which did not. In the wake of the agreement and the Laquan McDonald controversy, the number of stops has plunged – to 39,778 from January 1 through May 15, 2016, down 84.3 percent from 252,698 in the same period a year earlier. Only 6,307 of this year’s stops, or 15.8 percent, ended in arrests, city records show.

The ACLU agreement probably is not the only factor behind the drop in stops. Dean Angelo Sr., president of the Chicago chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police, contends that in the aftermath of the Laquan McDonald shooting, the time-honored anti-crime political mantra has given way to an anti-police mantra that discourages some officers from making stops because they fear being accused of racism. That, he said, will in turn put the public at increased risk.

“What’s actually more striking than anything else is just how normal and ordinary it has become for black students to be stopped under the suspicion of being a criminal.”

Chicago police spokesman Frank Giancamilli says that the number of stops has begun to rise slowly in recent weeks, but that the number will remain far below the previous level, as officers focus on “making sure we’re stopping people for the right reasons.”

If Giancamilli is correct, stopping people for the right reasons will be welcomed by the accountability task force, which found “substantial evidence that people of color – particularly African Americans – have had disproportionately negative experiences with the police over an extended period of time” and “that these experiences continue today [as a result of]. . . practices that disproportionately affect and often show little respect for people of color.”

Jonathan M. Smith, who until 2015 was responsible for investigating patterns and practices of troubled police departments for the U.S. Department of Justice, says that aggressive use of stop-and-frisk “creates this enormous rift in communities and a real unwillingness to call and cooperate with police when something serious is happening.”

While aggressive policing alienates communities, considerable research shows that it also deters crime. Based on an exhaustive study, Franklin Zimring, a noted criminologist and law professor at the University of California Berkeley, attributes New York City’s drop in felonies, which was roughly twice the average decline nationally from 1990 through 2010, solely to the city’s proactive policing policies.

Eugene O’Donnell, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and veteran New York City police officer, says there is no question that aggressive policing reduces crime. As he puts it, “If you don’t do that in a city like Chicago, especially now, the bad guys are absolutely aware it’s free reign.”

The situation poses a dilemma for city officials, who at once hope to rebuild public trust in the police and aggressively fight crime, which is expected to rise as temperatures rise this summer.

“Striking that right balance is important,” says Lori Lightfoot, president of the Chicago Police Board and member of the accountability task force, who hastens to add that the challenge is to do it “in a way that engages, and doesn’t alienate, communities.”

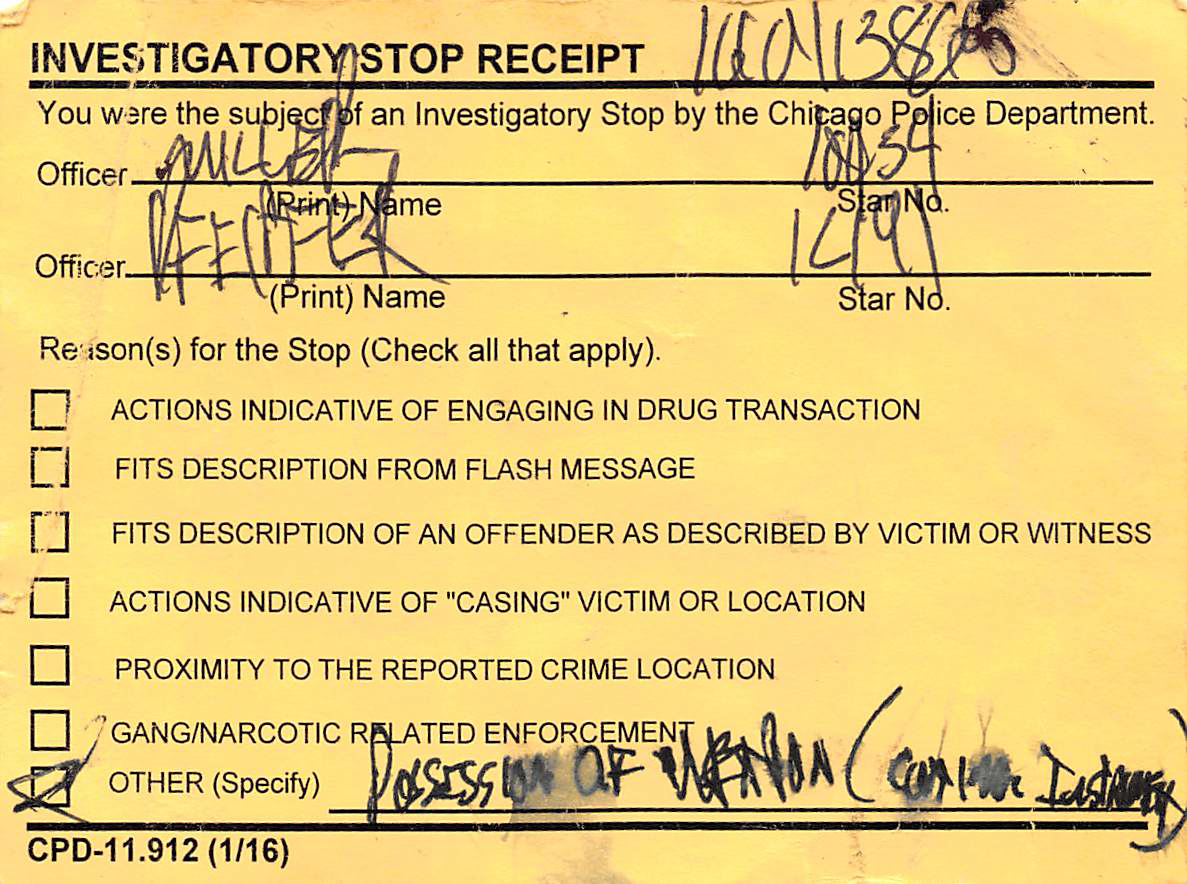

Not all stops recorded

Defense attorneys say that for years the police have made untold numbers of unrecorded stops -- so-called “dark stops.”

In May, the city agreed to pay $40,000 to settle a federal lawsuit brought by Larry Nelson, the 24th Ward Republican committeeman, over an incident that police at first denied took place. After Nelson’s attorney, Irene K. Dymkar, discovered that police had run Nelson’s name through the Secretary of State’s database to check for warrants – leaving no doubt that they had stopped him -- the officers revised their story, contending that they had no recollection of the stop.

Larry G. Nelson and Attorney Irene K. Dymkar (right). While Nelson contends he was stopped by police in February 2008, officers in court denied remembering the stop. Photo by Gabrielle Morris/Injustice Watch

Dark stops apparently are quite frequent. Dymkar found that on the very night Nelson was stopped, police ran 44 other warrant checks on individuals for whom there was no record of stops. Dykmar says she has several other clients who claim to have been stopped and searched, although no records of the encounters exist.

Not documenting stops “is a really big problem,” says Dymkar.

Romanucci, the lawyer representing Smith and others in the federal class-action, says the number of dark stops may be substantial, given that several of his clients report that they never have seen police fill out forms during or after searches.

RELATED: Read more about Larry Nelson

Police stops based on “reasonable suspicion”

Although the Fourth Amendment protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, the Supreme Court has struggled for decades to define what is and isn’t permissible, resulting in uncertainty that officers on the street sometimes find confounding.

As Mark Iris, a former executive director of the Chicago Police Board, puts it: “Even a conscientious, well‐intentioned officer is going to be hard‐pressed sometimes to keep up with the nuances of what is and what is not a legal search. And unlike the justices on the Supreme Court, they don’t have months to deliberate this with a squad of law clerks.”

In a case known as Terry v. Ohio, the Supreme Court held in 1968 that officers may approach individuals on the street, pat them down for weapons based on “reasonable suspicion” – a lesser standard than “probable cause” – and, if the officers feel what may be weapons, they may conduct full searches.

The case involved a Cleveland police detective who suspected that three men were casing a downtown store to rob. The detective questioned the men, then patted them down, and, feeling what he thought were weapons on two of the men, searched them and found guns. Those men, John W. Terry and Richard Chilton, were convicted of carrying concealed weapons. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Supreme Court upheld the convictions, legalizing what became known as “Terry stops.”

Subsequent cases have extended the search authority beyond street stops first to traffic stops if officers reasonably suspect that drivers or passengers in cars might be armed, and then to car compartments if there is reasonable suspicion that occupants are armed and dangerous. In 2004, the Supreme Court upheld a Nevada law requiring individuals to identify themselves during Terry stops, but the ruling left it up to the states to create such laws. About half of the states have enacted such laws.

“Many innocent people are subjected to the humiliations of these unconstitutional searches.”

The latest case came last month when the Supreme Court held 5-3, with a majority opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, that even if officers lack reasonable suspicion justifying pat-downs, stops and seizures nevertheless become legal if the officers discover outstanding warrants against those stopped.

In an extraordinary dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor objected that “Many innocent people are subjected to the humiliations of these unconstitutional searches,” adding that “anyone’s dignity can be violated in this manner” and that, although those stopped in this case were white, “it is no secret that people of color are disproportionate victims of this type of scrutiny…”

Sotomayor continued: “For generations, black and brown parents have given their children ‘the talk’— instructing them never to run down the street; always keep your hands where they can be seen; do not even think of talking back to a stranger — all out of fear of how an officer with a gun will react to them. . .

“By legitimizing the conduct that produces this double consciousness, this case tells everyone. . . that your body is subject to invasion while courts excuse the violation of your rights. It implies that you are not a citizen of a democracy but the subject of a carceral [prison-like island] state, just waiting to be cataloged.”

Chicago police long have tested the limits

The ACLU study that led to the city’s 2015 agreement to do a better job training officers and keeping relevant records also documented long-standing problems of Chicago police stopping and searching persons on the street without reasonable suspicion.

In the 1980s, the Chicago police arrested tens of thousands of youths for “disorderly conduct,” mostly in African American and Latino neighborhoods, and then not bothering to show up in court when the cases were scheduled.

In the 1990s, the police arrested tens of thousands of youths on “gang loitering” charges, mostly African Americans or Latinos, until a lawsuit brought by the ACLU caused the law to be declared unconstitutional.

In 2003, the ACLU brought a lawsuit on behalf a group that included Olympic gold medalist Shani Davis, contending they had been subjected to a series of humiliating stops. As part of the lawsuit, the police agreed to begin keeping records of the stops and the basis for making them.

Despite that agreement, the ACLU found last year that officers often failed to offer adequate explanations of their supposed “reasonable suspicion.”