In 2002, the body of a woman was found in a shed next to an abandoned barn in rural southwest West Virginia. She was naked from the waist down, with a tank top rolled up under her arms and a pair of leopard print pants beside her.

An autopsy determined she was strangled to death.

For five years the case remained unsolved, until a 26-year-old man with learning disabilities and mental illness, including bipolar disorder, told state troopers that he and three other men had been involved in her death.

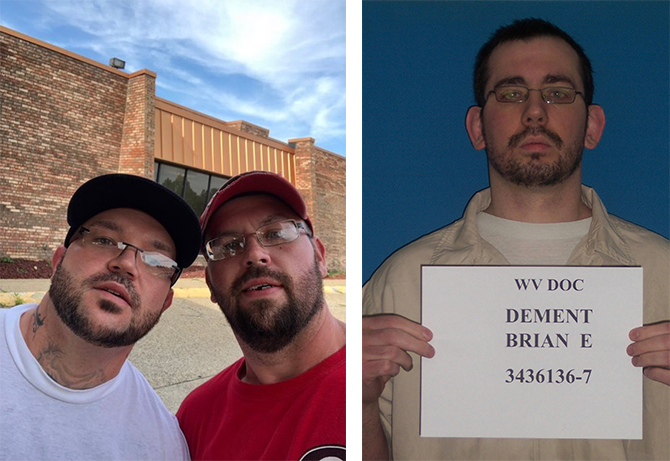

After confessing, Brian Dement agreed to plead guilty to the murder of Deanna Crawford, 21. His three associates all went on trial and, based largely on Dement’s statement, were also convicted of murder. Each was given a sentence of 30 or more years.

But two days after he pleaded guilty in 2007, Dement recanted his confession, saying he knew nothing about the crime but made up the story to satisfy authorities.

Then, last year, a surprising development occurred: DNA testing appeared to support his recantation, showing that the DNA of a convicted rapist was in semen found in the crotch of Crawford’s leopard print pants, as well as on a cigarette butt found near the shed.

The results of the DNA testing led a judge to overturn the convictions of Dement’s three associates.

But Dement has not been so lucky: Even though the physical evidence points to another man as the killer, so far the West Virginia judge has refused to grant a new trial for Dement, citing the fact that Dement confessed and entered a guilty plea.

“I wouldn't have had any problem at all if he would have pled not guilty and gone to trial and been convicted and then you find this DNA,” Cabell County Judge Alfred Ferguson said at a hearing on May 1. “He would have had a new trial. Just like the other defendants. But his case to me... is different from the other three because they have always maintained their innocence.”

CONFLICTING STATEMENTS

Nearly five years after Crawford was killed, Brian Dement’s uncle, a man with a history of prior convictions, brought to the West Virginia State Police tape recordings he had secretly made of Dement telling him that he and three other men had participated in Crawford’s murder.

Dement later contended he was “strung out on drugs” during the recorded conversation, and that his uncle likely fed him information “to get out [of] trouble himself.”

The state police brought Dement to the station and questioned him for nine hours, during which Dement provided three statements confessing to the murder and implicating Justin Black and brothers Philip and Nathan Barnett.

Dement’s confession never quite added up. The three statements he gave to law enforcement conflicted with each other; later, his version in court changed details yet again.

In all four versions, Dement contended that he, Justin Black, and Philip and Nathan Barnett left a party along with Crawford to go for a ride. In none of them did Dement say that he saw Crawford raped or even taken into the shed.

Instead, he said that after they had traveled a couple miles, one of the men punched Crawford, who was then dragged out of the car, repeatedly struck, and dragged into darkness. But who punched Crawford and who dragged her away conflicted from one version to the next. Dement’s descriptions of how he left the crime scene afterward also were contradictory.

Dement first told police that Black drove all four men at high speed back to his house, after which Dement walked to a nearby market and called a cab to his uncle’s house.

In his later statements to police, Dement said that the Barnetts and Black drove away without him. He said he then went to check on Crawford and found her body in the shed, lifeless.

He said he finally walked to his uncle’s house, which he said took about three hours. In fact, the uncle’s house is over 17 miles from the abandoned shed.

Then in court, Dement testified that he walked from the shed to the market, where he called the cab. The shed is almost six miles from the closest store and is about three miles up a steep, unpaved and unlit hill from the road where each of the four men lived at one time or another. An attorney for Black later established that no nearby cab companies were open at the time of the crime, and that no cabs even serviced this remote area.

PROSECUTORS PUSH FORWARD

There was no physical evidence found at the scene that linked Crawford’s death to Dement or any of his three associates: no DNA, no fingerprints or footprints, no clothing or hair fibers that would tie the suspects to the crime. Despite this lack of physical evidence as well as the inconsistencies in Dement’s statements, prosecutors pushed forward, charging all four men with murder but not with sexual assault despite evidence such an assault had occurred.

“To get convictions there had to be a cooperating witness,” said Joshua Tepfer of the Exoneration Project, who represents Black in post-conviction proceedings. “They needed someone to testify against the Barnetts at a minimum to get convictions, because there was no other evidence.”

Dement proved an easy target, since he had already confessed to the crime and was facing life in prison if convicted at trial.

“If somebody falsely confessed, all the more reason to plead guilty,” said Richard Leo, a professor of law and psychology at the University of San Francisco who specializes in the phenomenon of false confessions. “Because in our society, confessions are assumed to be true and accurate, because people assume no rational person would ever engage in the self-destructive act of falsely confessing, especially to a very serious crime.”

Facing a potential life sentence, Dement entered a guilty plea with the agreement that prosecutors would recommend a sentence of no more than 24 years.

West Virginia Circuit Judge John L. Cummings heard Dement’s plea and, despite the prosecutor’s recommendation, sentenced Dement to 30 years in prison.

Two days after Dement pleaded guilty, he told an investigator for Nathan Barnett that he had made up his confession, a recantation he has since repeated. In a recorded statement in October 2007, Dement told the investigator, Greg Cook, that he had been trying to “go against my statement” but that his lawyers and the judge did not allow him to do so.

More than a decade later, in a March 2018 interview with Martin Yant, another defense investigator, Dement reiterated that he had been forced into confessing and then pleading guilty. Dement told Yant he had told the prosecution that his statements were false and that he didn’t want to testify at the trials for Black and the Barnetts. But “the prosecutor, Chris Chiles, said I might as well go ahead and get on the stand and say what’s … in the statement, because regardless [of] if I do or don’t, we were going to get convicted.”

Dement added that the prosecutor told him he’d be in more trouble and “facing way more time” if he didn’t testify.

Black was tried first. The jury heard Dement’s accusation, and also that Dement had later disavowed his confession to investigators. The jurors also heard that Black himself had given an incriminating statement that he immediately recanted, saying that police had fed him details of the crime and threatened to revoke his parole if he did not tell them what they wanted to hear.

The jury found Black guilty of second-degree murder, and he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

The Barnetts went on trial together. Because Dement testified at their trial that his confessions contradicted each other and that he had given false information to police, Cummings ruled the jury did not need to also hear that Dement had begun recanting within days of his guilty plea.

The jury found the Barnett brothers guilty of second-degree murder. Philip and Nathan Barnett were sentenced to 40 years and 36 years, respectively.

On appeal, the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals upheld Black’s conviction but overturned the convictions of the Barnetts, ruling that Cummings had erred when he excluded the recantations that Dement had made to investigators well before trial.

SUSCEPTIBLE TO FALSE CONFESSION

Experts cite a series of reasons why Dement would have confessed to a crime he did not commit. Russell Covey, a law professor at Georgia State University, noted that Dement’s interrogation lasted nine hours, continuing into the early morning hours.

According to the court record, Dement had been diagnosed with learning disabilities, antisocial personality disorder, attention deficit disorder, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety, and received Social Security disability benefits due to his mental condition.

Leo noted that defendants with certain mental illnesses, those with intellectual disabilities and adolescents all are highly susceptible to false confessions.

“Those three groups of people are vastly disproportionately represented in the known universe of false confessions,” Leo said. “And there's lots of good research explaining why those people are so gullible, so easily manipulated, why it's so easy to confuse them and move them to agree to what you want them to do.”

Dement’s conditions each made him particularly susceptible to a false confession, experts said.

Allison Redlich, a professor in the department of criminology, law and society at George Mason University and a psychologist who studies false confessions and false guilty pleas, said suspects with attention deficit disorder may lack the impulse control to resist the temptation to agree with interrogators.

She said those suffering bipolar disorder also are vulnerable: “If they’re severely depressed, they may not really care what happens to them; if they’re manic, that will also impair their decision making.”

Leo said people with anxiety are vulnerable as well.

In his interview with investigator Yant last year, Dement said: “My mom died, and I just — I didn’t care anymore. I was in a messed-up relationship, and I’m not using that all as an excuse, I’m just saying, like, the timing was bad, and it was a false statement indeed.”

A PLEA AVOIDS RETRIAL

After the Barnetts’ convictions were overturned on appeal, prosecutors prepared to retry them -- creating the risk of being convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

But prosecutors offered an alternative to a second trial: If the Barnetts would agree that there was sufficient evidence that a jury might find them guilty, they would be allowed to enter a plea to the lesser crime of voluntary manslaughter while maintaining they were innocent. Such a plea, first endorsed in the 1970 U.S. Supreme Court case of North Carolina v. Alford, has created repeated instances of defendants left with criminal records despite substantial evidence of innocence.

Philip Barnett entered his Alford plea to the lesser charges of voluntary manslaughter and malicious wounding, and Ferguson sentenced him to a term of 7 to 25 years. Nathan, pleading only to voluntary manslaughter, received a sentence of 15 years.

Philip Barnett has said to a reporter for The Herald-Dispatch of Huntington, W.Va., that had he not been a father, he would have taken the risk of going to trial again.

Valena Beety of the West Virginia Innocence Project, who represented Nathan Barnett in post-conviction proceedings, said the brothers entered the pleas because they feared what could happen at trial.

“When you’ve already been convicted in a very weak case, and you don’t have new evidence that you’re putting forward, it’s definitely a risk,” Beety said. She added that the evidence in the case was already years old by the time law enforcement made arrests, and that the testimony of the state’s witnesses did not even make sense on a timeline.

However, often “confessions can trump evidence” at trial, according to Melissa Giggenbach of the West Virginia Innocence Project, who currently represents Nathan Barnett.

“People in general, and prosecutors in particular, are loath to believe that people falsely confess, or that they make false statements,” Giggenbach said. “It's just really hard for people to understand that someone would say something against their own self-interest.”

A BAD SMELL

In 2014, private investigator Yant became involved at the request of Black’s mother.

“It just did not smell right at all,” Yant said. “Four guys convicted of murder without any physical evidence at all. The victim lived on one side of town, they lived up in the hills on the other side of town … It just didn’t make a lot of sense.”

Attorneys from the Exoneration Project, the West Virginia Innocence Project and the national Innocence Project went to court seeking DNA testing on crime scene evidence on behalf of Black and the Barnetts. The motion was granted in September 2016.

West Virginia is one of only 15 states that explicitly allows defendants who pleaded guilty to pursue DNA testing to appeal their convictions at any time. Even though approximately 11% of the wrongful convictions proven by DNA in the United States involved a guilty plea, some states prohibit people who pleaded guilty from applying for DNA testing, or restrict their ability to do so through time limits and additional eligibility criteria.

In February 2018, the DNA tests came back with results Tepfer called “extraordinary.” DNA from semen on Crawford’s leopard print pants, as well as from a cigarette butt found near the isolated crime scene, pointed to Timothy Smith, a convicted child rapist who was incarcerated in an Ohio state prison at the time.

By then, Nathan Barnett, who had served eight years, had been out of prison on parole for three years.

According to Beety, the conviction that accompanied her client’s Alford plea made life after prison difficult. “It has been hard for Nathan, having this conviction and trying to move on with his life, and being rejected within his community, and actually needing to live somewhere else just to be away from all of it,” Beety said. “Even though he's been released from prison, you know, it just hangs over your life.”

Black was released on parole in June 2018 after serving 10 years in prison. Philip Barnett was released two months later on a $50,000 bond. Dement remains incarcerated, having served nearly 12 years so far.

EVIDENCE AGAINST SMITH

Yant followed up on the DNA tests by interviewing Smith and three of his former wives. Smith denied any knowledge of the crime. But the woman who was married to him at the time of the murder told Yant that around the time Crawford’s body was found, Smith had come home with blood on him and bloody money he couldn’t explain.

He later told her that he had killed someone. An ex-wife who married Smith two years after the murder also told investigators that Smith confessed to her that he’d killed a woman in West Virginia in 2002. All three of Smith’s ex-wives told Yant that he had physically abused them, sometimes so severely that they were hospitalized and prescribed pain pills, which he would then take for himself.

Despite these ex-wives’ statements and the DNA evidence linking Smith to the murder, the state has not yet brought any charges against him in relation to this crime.

Whether or not the state brings charges against Smith, the DNA evidence made a huge difference in the cases against Black and the Barnett brothers. On May 1, Judge Ferguson vacated the convictions for Black and the Barnetts, deciding that the DNA findings entitled the three men to new trials.

“Of course, I would never want a person who is innocent to be locked up. And I’m sure you all would not either,” the judge said to Crawford’s family, who have indicated their beliefs that Dement, Black, and the Barnetts are guilty, despite the DNA evidence. “You want justice. The prosecutor wants justice. Everybody in this room wants justice. The court certainly wants justice.”

Karen Thompson, a former lawyer at the national Innocence Project who represented Philip Barnett in post-conviction proceedings, described this as “a textbook case” of wrongful conviction, noting that “we have a body, we had semen from that body, it was a single source male, it was a lot of semen, and it hit to a man with a dissertation-long rap sheet — that included rape, that included intense violence against women — who was incarcerated.”

But Dement remains locked up, which Beety calls “the most disturbing part” of the whole case. While he granted new trials for the other three men, Judge Ferguson ruled that Dement is not entitled to a new trial because of his plea and confessions.

The judge, who told the courtroom audience he rules “from the hip,” acknowledged that the West Virginia Supreme Court might disagree with him. “If the Supreme Court grants him a new trial, then so be it,” Ferguson said. “He certainly has a right to appeal that to the Supreme Court. And hopefully if you all really believe what you are saying, you will do that.”

Thompson said the case reveals “a real brokenness” in a criminal justice system that relies on pleas. Leo, the expert on false confessions, agreed. “It's an unfair, unjust system that all too often leads to innocent people being wrongfully convicted.”